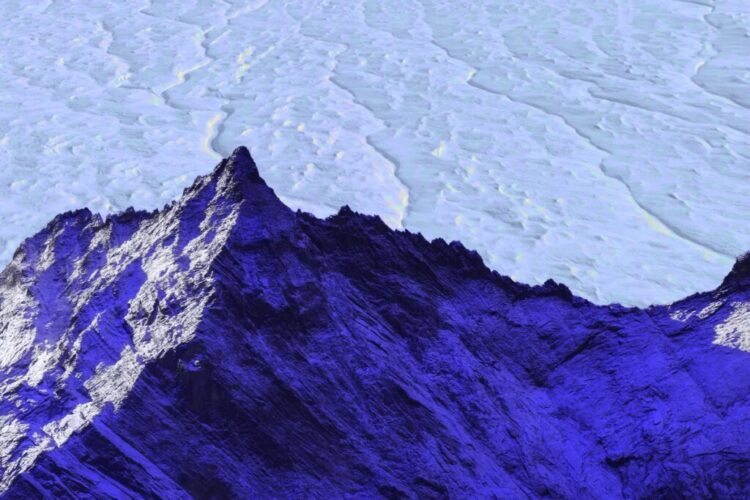

In a groundbreaking study published in Science, researchers have revealed a hidden landscape beneath Antarctica’s vast ice sheets, uncovering hills, ridges, and entire mountain ranges previously unknown. “It’s like before you had a grainy pixel film camera, and now you’ve got a properly zoomed-in digital image of what’s really going on,” said lead author Helen Ockenden of the University of Grenoble-Alpes, highlighting the unprecedented clarity provided by a combination of satellite optical images, radar data, and ice-flow modeling.

Traditional radar surveys on the ground, which could only capture snapshots of the frozen continent miles apart, left vast gaps in knowledge, with coauthor Robert Bingham of the University of Edinburgh comparing it to imagining the Scottish Highlands or Alps hidden under miles of ice, where occasional flights could never reveal the full topography.

The study’s new approach revealed a highly varied terrain of alpine valleys, eroded lowlands, and networks of channels carved by water flow spanning hundreds of miles, offering insights into Antarctica’s subsurface features and where future radar surveys should focus. “We’re not so blind now,” Bingham told Science, emphasizing that while the technique cannot resolve features smaller than a few meters, it provides an invaluable map for understanding bedrock roughness and planning detailed exploration. Duncan Young, a glaciologist at the University of Texas at Austin, noted the method’s limitations but agreed it significantly improves the scientific picture of Antarctica’s hidden geography.

Understanding these subterranean landscapes is critical for predicting how the continent’s ice sheets will respond to climate change, particularly near the Thwaites Glacier, whose previously hidden base is now known to be exposed to warming seawater. “If just one ice sheet collapses, sea levels could rise by dozens of feet in the coming centuries,” the study warns, underscoring the urgent need to map and monitor Antarctica’s frozen interior. The new imaging techniques promise to reshape scientists’ understanding of the continent, providing crucial data for climate models and future predictions of global sea-level rise.